My father Harry only saved a few mementos of his early life. He was not interested in family history and when I asked him about writing his memories for posterity, he replied, “Why would posterity be interested?” But he did save two things, carefully packing and taking them along on his many moves. They were his diploma from Tyrone High School in 1935 and his chemical engineering degree from Penn State in 1940. His father John had graduated from Tyrone High School in 1905, and that was enough to get him what passed for a white-collar job at the time, a clerk for the Pennsylvania Railroad, the “Pennsy” as it was called. John made enough money to buy a house and support his family, and he must have pushed his four sons to follow in his footsteps. The oldest son, David, went to Juniata College, and then on to become a Methodist minister. The second son, Joe, became an engineer for Pratt and Whitney, but did not graduate from college.

My father aimed higher. Rather than going to a regional school like Juniata, he chose to go to Penn State and enroll in the school of chemical engineering. It was a brave choice and a hard one. The family lost their savings when the Tyrone bank failed in the crash of 1929. My father told several stories about what he had to do to go to Penn State. He hitched a ride with the mailman in the morning to get to State College, getting up at four o’clock in the morning to be on time. To pay his expenses he washed dishes and peeled potatoes in a fraternity. And he got a grant from the National Youth Administration, paying him the princely salary of twenty-five cents an hour – a grant he claimed was responsible for his lifelong liberal politics. He earned the salary by washing glassware in the chemistry lab, “the amines with their fishy smell” and later by helping Dr. Rose run chemistry experiments. Whatever sacrifices Harry made must have seemed worth it when he graduated in the spring of 1940, as one of forty-one students to graduate in chemical engineering that year, all men of course, in the custom of the time. He remembered it as only thirteen graduates, out of the 200 who started in the program. Either way it was an impressive achievement for a poor boy from a small town.

He must have gotten a job offer just after graduation, since by the fall of 1940 he was living and working in Germantown, Pennsylvania. The job was with Fischer and Porter, a company making instrumentation systems, which would be my father’s specialty his entire working life. The company had been founded a few years before by Kermit Fischer, and they made rotameters, devices to measure flow. Harry worked for Kermit Fischer for several years before something soured between them. As my mother put it, in a letter to her mother, both of his jobs were “hazardous relations”. He was then living north of the city and taking the bus into Philadelphia during the evenings, taking classes toward a medical degree, but after America joined the war there was a shortage of instructors, and the classes he needed were only given during the day. Of course he couldn’t afford to quit his job to take classes full time.

My father then got a job with a competitor, another company that made rotameters. This was Brooks, started in 1946 by Stephen Brooks, a “fledgling company” as my father later told me. Brooks had a new design for rotameters – a “side-plate, dowel-pin construction”. It’s possible that Stephen lured my father away from Kermit Fischer, which makes me wonder about industrial property rights and non-disclosure agreements, but my father was an upright man, honest to the bone, and would not have spilled other people’s secrets.

He worked for Brooks until 1948, when he and my mother decided to move to California in hopes of improving her asthma. They believed that a dry climate would be better for her, so they packed up and left for El Centro, at the southern end of Death Valley, where my father got a job with U.S. Gypsum. He had been promised a job that would take advantage of his engineering skills, but when he got there, he found himself making gypsum wallboard. They did not have a car and he had to hitchhike or find a ride to work, and it was the most miserable year of their lives. My mother was home alone with a toddler (me) and pregnant with my younger sister, far from her friends and family. My father formed a life-long hatred of the desert. They barely scraped by, but the country was in a postwar recession and he could find nothing better. Finally, as the last straw, my mother’s asthma took a turn for the worse and they decided to move back to Pennsylvania.

Kermit Fischer had made one last attempt to hire my father back while they were still in California. He wrote a letter, very “sweet” as my mother put it, asking Harry to meet with the company vice president in San Diego. My father believed that this was an attempt to pump him for information, possibly about Brooks and its rotameters, and he refused to go. Apparently Kermit was spreading a rumor about my father, probably that he was coming back to Fischer and Porter. As my mother put it, “We think Kermit spread the news to hurt Harry’s chances locally and the news would naturally infuriate Steve so that’s just plain revenge. … all I can say is that he won’t ever go back to Fischer and Porter and (almost as positively) never go back to Brooks Rotameter.”

After they moved back, my father worked for Minneapolis Honeywell, the thermostat company. He never talked about those years, and I was too young to remember anything, since I was living with my aunt and uncle up in Woolrich, a small town far from Montgomery County where my parents were. He must have owned a car by then, since he would come up on weekends to see me. My mother died in May of 1952 and he was a single father for two years, until he remarried in 1954, and we all went to live in Philadelphia.

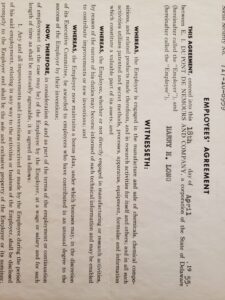

When my father got a job offer from DuPont in the spring of 1955, he must have felt that his ship had come in. Finally he would be working for a company that provided security, a good salary with benefits including medical care and a pension. It was truly his ticket to the middle class. He signed a non-disclosure agreement with DuPont on April 18, 1955, agreeing that any “improvements and inventions” he made as an employee would be the property of DuPont, and also agreeing not to disclose any “secret or confidential information”. My dad was a careful man and he saved that agreement for the next fifty years.

He worked at first at the Chambers Works, a sprawling manufacturing plant in Bridgewater, New Jersey, a half-hour drive from our new house in Brookside Park, outside Newark Delaware. The Chambers Works was tucked in next to the Delaware Memorial Bridge, and whenever we went over the bridge on our way to New York City, I would always look for my father’s building, a tiny two-story building in the very back left corner of the Works, hard to spot in the large plant. Four years later he was transferred to Jackson Labs, a separate department in the same location, as a senior research engineer.

Unfortunately, and there is no way to sugar-coat this, the Jackson Labs was responsible for the development of four main products: tetraethyl lead, Teflon, coal tar dyes, and fluorocarbon refrigerants. At the time, these fell under the rubric of DuPont’s motto of “Better Living through Chemistry”, but we now know that they were harmful for the environment and for living things. Chlorofluorocarbons were “once hailed as a pinnacle of 20th century industrial chemistry. CFCs showed up in refrigerators, aerosol cans, and solvents of all kind. They were everywhere, like some sort of miracle compound specifically designed for modern consumerism.” Tetraethyl lead is now banned as an additive for car gasoline; coal tar dyes are banned in some places, as is Teflon; CFCs are banned from refrigerants and aerosols. When I asked my father how he felt about his work, years after he had retired, he shrugged. As an intelligent man who read newspapers, he would have seen the implications, but if he felt any great remorse, he did not share it with me.

Toward the end of his working life with DuPont, when he only had to commute a few miles over to the Louviers Building, my dad was sent down to Louisiana, where DuPont was building a new plant. He was in charge of the instrumentation for the plant, designing where the instruments would be placed to analyze the chemicals as they were made. He was proud of this assignment, which showed the confidence the company placed in him.

When he retired in 1955, DuPont gave him a red binder with a portrait, pages of good wishes from his co-workers, and sheets with cards from friends and family. This was another of the few artifacts he saved down through the years, showing how much his work meant to him.

Sources:

Obituary of Kermit Fischer, died 1971, a New York Times obituary.

History of Brooks Instrument Company, on their website at https://www.brooksinstrument.com/, accessed 2022.

Personal Communications from Harry Long, 1982, 1993-94.

Letters written by Dorothy Long to her mother Helen Tyson from El Centro, California, 1948-49.

Image of a Brooks Rotameter from EBay.

History of the Jackson Laboratory, at https://snaccooperative.org/ark:/99166/w6rp1scc.

Article by Neel Patel on CFCs, Popular Science, 2018, at https://www.popsci.com/cfc-ozone-emission/.

A clipping from a DuPont publication on the occasion of Harry’s retirement.

The few books Harry saved: his high school and college yearbooks, his red retirement binder, his chemistry handbooks.

Note: My dad said that there were only thirteen graduates in the chemical engineering program in 1940, but the graduation program lists forty-one. Perhaps the chemical engineers were distinct from the chemists.

timeline:

born May 1917

graduated from Tyrone High School in May 1935

graduated from Penn State in June 1940; was it normal to need 5 years?

1940 draft card: Living in Germantown, working at Fischer & Porter

1942: probably still at F & P, saved the group picture from 1942, from a F&P newsletter

June 1943, married Dorothy

after that, probably lived in Hatboro

between 1946 & fall 1948, worked for Steve Brooks at Brooks Rotameter, possibly recruited soon after 1946, when Brooks founded the company.

1948, got a job with U.S. Gypsum, moved to El Centro

spring 1949, recession still on, moved back to Pennsylvania

May 1952, Dorothy died.

Where did he live?

Married Hildegarde around 1954, when I was in 2nd grade

Moved to Philadelphia

I remember my dad coming up to visit me on the weekends, but I never saw my mother again. My sister was living with my mother’s parents Raymond and Helen in Perkasie. Nowadays a single dad might keep two young children with the aid of paid help, but in the 1950s it was assumed that young children needed a mother figure.